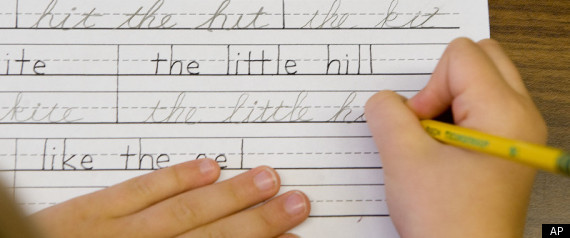

Schools Debate Cursive Handwriting Instruction Nationwide

Cursive handwriting instruction is disappearing.

Students and teachers alike have swapped pencils for keyboards, baselines for blinking cursors, and have all but written off the traditional route of writing.

Although standardized tests may not pick up the flourish of a cursive capital "T" or grade against floaters and sinkers, proponents of cursive handwriting maintain that there is value in teaching the craft and hope to save it from being erased from educational relevancy.

ABC News reports that 41 states have adopted the Common Core State Standards for English, which omits cursive handwriting from required curriculum. Now that it's not mandatory, schools around the country are debating whether or not to spend valuable teaching resources on penmanship.

In New York, some schools are considering cutting it altogether. Deb Fitzgerald, a second-grade teacher at Van Schaick Elementary in Cohoes, told CBS 6 Albany that she'd rather "move on" and focus class time on other topics.

WATCH:

Cindee Will, assistant principal at James Irwin Charter Elementary School of Colorado Springs, maintains that choosing to teach cursive is not about aesthetics or preference, but about giving children the mental tools needed to read English. She explained to the Denver Post that the threaded letter strokes help guide students' eyes left-to-right and definitively correlates reading with writing:

Carnegie Mellon University's print analysis program, reCaptcha, was developed to make print texts searchable through digitization. However, when it comes to old handwritten manuscripts, the best translations are done with human eyes, reports The New York Times.

Whether or not the next generation will be taught to read those manuscripts remains to be seen. Luis von Ahn, a computer scientist involved with the reCaptcha project, echoes a familiar sentiment:

Students and teachers alike have swapped pencils for keyboards, baselines for blinking cursors, and have all but written off the traditional route of writing.

Although standardized tests may not pick up the flourish of a cursive capital "T" or grade against floaters and sinkers, proponents of cursive handwriting maintain that there is value in teaching the craft and hope to save it from being erased from educational relevancy.

ABC News reports that 41 states have adopted the Common Core State Standards for English, which omits cursive handwriting from required curriculum. Now that it's not mandatory, schools around the country are debating whether or not to spend valuable teaching resources on penmanship.

In New York, some schools are considering cutting it altogether. Deb Fitzgerald, a second-grade teacher at Van Schaick Elementary in Cohoes, told CBS 6 Albany that she'd rather "move on" and focus class time on other topics.

WATCH:

However, just as there are two loops in a cursive capital S, there's another side to the debate.

"In many respects, it's only inside our schools where we see such emphasis on paper and pencil," she says. "The move outside our schools, and in innovative schools, is toward technology. There will always be a role for the written word by hand on paper. But the experiences most of us have, with 30 minutes a day practicing cursive in class, has gone by the wayside."

Cindee Will, assistant principal at James Irwin Charter Elementary School of Colorado Springs, maintains that choosing to teach cursive is not about aesthetics or preference, but about giving children the mental tools needed to read English. She explained to the Denver Post that the threaded letter strokes help guide students' eyes left-to-right and definitively correlates reading with writing:

That rationale is intensely applied at Camperdown Academy in Greenville, S.C., a private school that teaches dyslexic children how to cope with their learning disabilities. WYFF reports that Camperdown teachers use cursive handwriting extensively, as the built-in mechanics of the craft teach students how to group words in the proper order and make it more difficult to swap letters. One teacher told WYFF:

"When kids get to third and fourth grade, when they're supposed to be composing, they can use more brain space for content than mechanics," Will says.

"They do so much better if they can interact with what it is they're learning."To some, the interactivity of cursive not only relates to the physical act of writing, but to community and heritage. When Pam Bates found out that handwriting would no longer be taught at her daughter's school, she had to take action. Bates started a cursive club and now helps 40 other students craft their writing by upholding a time-honored tradition. She told the Denver Post:

"I absolutely get that we're moving in a world that's technology-based," she says. "But I'm of the old school that believes you can't forget where you came from to get where you're going. There could be a day the computer crashes."Although it seems technology could be called the enemy of cursive, it still can't quite conquer the written word.

Carnegie Mellon University's print analysis program, reCaptcha, was developed to make print texts searchable through digitization. However, when it comes to old handwritten manuscripts, the best translations are done with human eyes, reports The New York Times.

Whether or not the next generation will be taught to read those manuscripts remains to be seen. Luis von Ahn, a computer scientist involved with the reCaptcha project, echoes a familiar sentiment:

"Nobody reads handwriting anymore."

No comments:

Post a Comment